The last words of the new documentary-style film “AKA Jane Roe,” one filmmaker’s version of the life of the woman behind the Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion throughout the United States, are those of Norma McCorvey (“Jane Roe”) herself. Due to the nature of the film, the connections of the filmmakers to Planned Parenthood, and the heavy editing, many things in the documentary remain unclear. The film jumps back and forth, using older clips of McCorvey from decades ago, spliced and edited together with footage filmed closer to her death, making it difficult to determine the context of many of her statements. But the one thing that is true is that the film’s final words embody who Norma McCorvey was:

It’s my mind. They can’t tell me how to think. They can’t tell me what to say. And they damn sure can’t tell me what to do. That’s the name of that game.

Filmmaker Nick Sweeney would have viewers believe that McCorvey was speaking about pro-lifers, but without the unedited footage, there is no way to know she wasn’t speaking about the abortion lobby, or even about people in general. No one could tell Norma McCorvey what to do or say or think and she seemed to keep everyone on their toes. And the game? It seems the abortion lobby’s attempt to use McCorvey as a political pawn one more time is the final play.

The film reveals details about McCorvey’s difficult childhood without her father and with a mother who made her feel “insignificant and worthless” and beat her. From there—reform school, sexual abuse by a relative, marriage at age 16 to a 22-year-old man who hit her, and unexpected pregnancy all deeply affected her. She was ridiculed by her mother for being a lesbian and lost custody of her daughter to her mother. She had been so hurt and damaged by the adults around her that it’s a miracle she survived.

But for McCorvey, life had always been about survival, and always would be.

“She was no poster girl…”

As the film progressed, it actually demonstrated how the abortion lobby used McCorvey and then collectively washed its hands of her.

“They needed a poor woman who could not afford to travel to one of the states where abortion was legal,” said long-time abortion proponent and counselor Charlotte Taft in the film. The abortion lobby needed McCorvey, but they didn’t help her. The young lawyers behind Roe v. Wade —Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee—used McCorvey’s signed affidavit to legalize abortion, but McCorvey herself never went to court. In 1973, after her baby girl had already been born and placed for adoption, the Supreme Court legalized abortion based on her case.

“My phone rang. It was Sarah, and she said, ‘We won,’ and I said, ‘No, Sarah, you won.’ She says, ‘Well I thought that maybe you would be excited.’ I said, ‘Why would I be excited? I had a baby, but I gave her away,”’ McCorvey recalls in the film. Already, she knew she had been used.

Taft further revealed that McCorvey “was no poster girl that would have been helpful to the pro-choice movement,” adding, “an articulate, educated person could not have been the plaintiff of Roe v. Wade.”

About a decade later, after coming out publicly as Jane Roe, McCorvey spent some time on the pro-choice side, but in the film, it is evident that she was never the image the pro-abortion cause wanted, even though she had teamed up with famous pro-abortion attorney Gloria Allred. McCorvey began working as an abortion counselor at A Choice for Women, an abortion business in Dallas, alongside her partner Connie. There, she said she told women, “As long as you think you’re doing right, then you’re doing right.”

Of the pro-lifers who stood outside that abortion facility, including pro-life group Operation Rescue (which had moved in next door), she said, “I told them they were damn liars and that they better check with their God to make sure that they were still gonna go to heaven.” It appeared that the filmmakers tried to portray these words as if they were McCorvey’s thoughts at the time of filming, but these were recollections from her past.

Flip Benham (Screenshot: Carole Novielli)

When McCorvey spoke to the filmmakers specifically of Flip Benham, an evangelical minister and former national director of Operation Rescue, it was clear that she respected him. When Benham and McCorvey first began talking outside the abortion business in the mid-90s, Benham told her about his own past pro-abortion beliefs. McCorvey said, “And that’s when he gave me his testimony and he was a badass, a sinner just like everyone else, womanizer. He did it all. It’s kind of like my life. […] Then he, he just fell kind of quiet, and he said, ‘Do you like what you’re doing?'” The look on her face in the film shows that she clearly didn’t like working in the abortion industry. Having finally seen it from the inside, she didn’t like what she saw.

“Used” by pro-lifers?

Reverend Rob Schenck, who was once pro-life, was around for McCorvey’s pro-life conversion. In the film, he said her conversion “was like being given the Academy award. She was our Oscar and we were gonna put her on the mantel and show her off to the world.” He added, “I set out immediately to bring her to Washington D.C. and put her on a national stage. There was nobody like Norma in our movement, nobody.” The key word in that statement is “I.” Was it Schenck alone who saw her as something other than a human being—a trophy to be captured and used?

Benham maintained that McCorvey was not a trophy to him, but a “gift from God.”

Old footage shown in the documentary quoted McCorvey saying she viewed pro-life speaking as “an opportunity.” The abortion lobby never saw her as worthy enough to have a spot on their stage. That was reserved for the likes of Cybill Sheppard and Whoopi Goldberg, not women like McCorvey.

“The prolifers have shown me what it’s like to be a human being for the very first time in my whole life,” she said shortly after her conversion, with obvious joy on her face. “They’ve loved me. They’ve nurtured me and they’ve cared for me. I’ve never felt so good about being a woman or about being just a person than I have from these people.”

Rev. Schenck has since recanted his own pro-life beliefs. He claimed in the documentary that Norma was forced to hide her relationship with Connie, but that relationship was a well-known fact. When McCorvey was baptized by Flip Benham, Connie was present, and the two lived together—some believe platonically—for another decade. “I loved her. I did. I loved her with all my heart,” McCorvey said of Connie in the film. “She was a good person.”

Pro-lifers like Benham welcomed McCorvey with open arms. In an interview for Nightline with Ted Koppel in the 1990s, Koppel pressed her on whether she believed the pro-life movement would use her like the pro-abortion side did. She told him, “No, sir! And I will not let them use me.” McCorvey was now fighting on the pro-life side and it upset the abortion lobby.

Was Norma “paid” to switch sides?

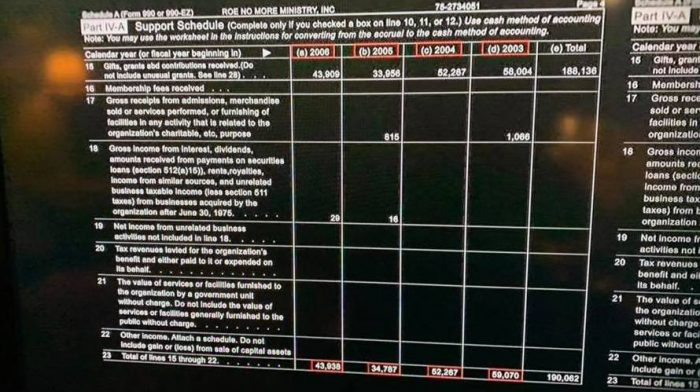

While the “AKA Jane Roe” filmmakers said they discovered documents detailing more than $450,000 in “benevolent gifts” given to McCorvey by pro-life groups, it appears that this amount was received over several years.

Screenshot courtesy of Carole Novielli

Benevolent gifts don’t point to McCorvey being ‘bought’ by the pro-life movement. McCorvey was paid honorariums for speaking engagements, and once she ended her years of public speaking, charitable gifts were given to her ministry to help pay bills and keep food on the table, her long-time friend Karen Garnett told Live Action News.

McCorvey’s friend, attorney Allan Parker, represented McCorvey for free over 12 years as she sought to have Roe v. Wade overturned, paying only for her court-related travel expenses and the like—none of which was income for McCorvey. According to Parker, who spoke to Live Action News, she was dedicated to undoing the Supreme Court decision that bore her name.

Benham told Live Action News that before McCorvey left her job at the Dallas abortion facility in the 1990s, he told her what he told all of the abortion workers: “If you come out, we’ll take care of you. You will not be left alone. We’ll help you find a job.” It was the same with McCorvey. “We took care of her,” he said.

Eventually, they also helped her find a publisher for her book, and she received money from the sales, Benham said. According to biographer Joshua Prager, this amounted to around $80,000. In addition, McCorvey was usually paid to speak at events, which is standard practice. Yet, in an interview with The Daily Beast, filmmaker Sweeney called these sources of income “a very elaborate and creative way” to pay McCorvey off. In reality, people with a story to tell typically receive income from their books and speaking engagements. There’s nothing elaborate or creative about it.

It appears the only person close to McCorvey during her conversion who claims the pro-life movement had McCorvey “on the payroll” to lie about being pro-life is Rev. Rob Schenck.

Was it all “an act”?

“This is my deathbed confession,” McCorvey joked towards the ending of the documentary’s filming after asking for oxygen and taking deep breaths.

“Did they use you as a trophy?” the filmmakers asked her.

“Of course, I was the big fish,” she replied. When asked if she used them in return, she said, “Well I think it was a mutual thing. You know I took their money and they took me out in front of the cameras and told me what to say and that’s what I’d say.”

The filmmakers ask her for an example of what she would say, and McCorvey responded, “We’ve gathered here today to pay homage to the children that are being aborted in this abortuary. We’re doing this because abortion is wrong and I as the former Jane Roe of Roe versus Wade do regret signing that affidavit for the pro-abortion camps.”

“And it was all an act?” they asked.

“Yeah, I did it well, too,” she replied “I am a good actress. Of course, I’m not acting now.”

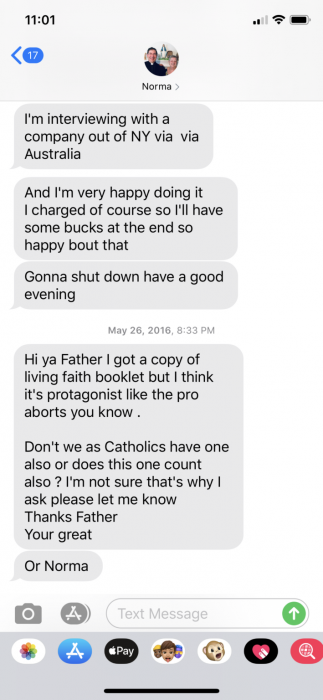

Or was she? McCorvey’s close friend and spiritual advisor Father Frank Pavone revealed this week that McCorvey was texting him the day that the filmmaker was arriving to begin filming “AKA Jane Roe,” and told Pavone she was being paid to participate (see text below). Filmmaker Sweeney, however, told The Daily Beast that McCorvey wasn’t paid for her participation in the project. It seems highly implausible that a woman who was struggling financially would not be paid to film a story about her own life.

Text message from Norma McCorvey to Father Frank Pavone in May 2016.

Pavone also stated that McCorvey had been upset with some pro-lifers at the time, and may have vented her frustrations on camera. For 22 years she worked alongside pro-lifers, and in the last years of her life she even lived with them.

According to those friends, McCorvey was deeply pro-life and well-loved by those in the pro-life movement who befriended her. “We loved her,” said Karen Garnett. “She was a complex and fragile person, but we loved her,” she told Live Action News. “Never once was there any indication that she wasn’t 100 percent pro-life after her conversion.”

Edited clips make context difficult to determine

Filmmakers captured McCorvey on camera making statements that may lead viewers to question whether she was truly pro-life. Yet without the unedited video and context, it’s impossible to know the whole story—were those her thoughts in 2016 while they were filming, or was she reminiscing of her pro-choice days?

“Women have been having abortions for thousands of years,” she said. “If it’s just the woman’s choice and she chooses to have an abortion then it should be safe. Roe versus Wade helped save women’s lives.” Additionally, she said in the film, “If a young woman wants to have an abortion, fine, you know, it’s no skin off my ass, you know. That’s why they call it ‘choice’. It’s your choice.” Was McCorvey speaking about her past pro-choice feelings here, or of her feelings at the time of filming? It’s unclear.

But McCorvey’s closest friends have noted that every time January rolled around each year, she became sad, and blamed herself for the deaths of a million more babies. McCorvey’s friend Karen Garnett was with her for three nights as she was facing her final days and being moved to hospice. According to Garnett:

“I could tell that she was looking at something that I couldn’t see,” she explained as she prayed at McCorvey’s bedside. “She said, ‘Look at the babies. Do you see the babies?’ And she reached her arms out as if she were embracing someone. I couldn’t see anything. She was so peaceful.”

McCorvey’s daughter even asked Garnett to speak at her mother’s funeral. These revelations don’t make McCorvey sound like a woman who was supportive of abortion.

(L to R): Pastor Flip Benham, Fr. Frank Pavone, Rev. Rob Schenck at McCorvey’s funeral (Screenshot: Carole Novielli)

In the film, McCorvey told filmmakers in a sad tone, “No, Roe isn’t going anywhere, no.” The film then cuts to her at a different point, stating, “It’s not going to be tampered with. They can try, but it’s not happening, baby.” Due to these edits, it is unclear if she is still talking about Roe here, if she is speaking of past feelings, or if she’s speaking of the pro-life movement.

Forgetting Jane Roe

McCorvey had spent the better part of 40 years known to America as “Jane Roe.” She knew she was close to dying when she filmed the documentary, and it was clear she didn’t want to be Jane Roe anymore—and hadn’t wanted to be for a long time.

“I was here five months before they even got a handle on me and I was very happy just being Norma McCorvey but now that they know that I’m Jane Roe or aka Jane Roe, I feel as though they look at me differently,” McCorvey told the filmmakers about life in the nursing home. She clearly no longer had the desire to be known in her daily life as “Jane Roe.” And those feelings were brought up at her funeral by her daughter Melissa, who said McCorvey decided to do this final documentary to show people who she really was: Norma, a person.

McCorvey’s closest friends and family, who were by her side until her death, do not appear to have been interviewed for the documentary. Yet the filmmaker attempted to paint a picture of McCorvey as a woman who changed her convictions based on paychecks. But McCorvey didn’t die as a woman of wealth or glory. She died a humble woman with a troubled past, who with her last breaths was apparently still thinking of the babies who had died because of Roe v. Wade.

“Like” Live Action News on Facebook for more pro-life news and commentary!