It was the best of times (for abortionists). It was the worst of times (for babies).

The House Select Panel on Infant Lives produced a 291-page document that was used to refer the University of New Mexico to the state’s attorney general for potential criminal charges regarding alleged fetal tissue donation violations. The background of the University of New Mexico’s involvement in abortion is revealed to be a focused plot between two doctors. Two persistent, abortion-focused doctors, Doctor #1 and Doctor #2, were the masterminds in a massive abortion plan.

The report states:

Before 2000, neither the University of New Mexico (“UNM”) Hospital nor any of its clinics offered abortions except in limited circumstances. Abortions were not performed except in rare cases of fetal anomaly or certain threats to a pregnant woman’s health—and then only in the hospital’s labor and delivery or operating rooms. When abortions were performed, nursing personnel and anesthesiologists were often unwilling to participate.1

UNM’s practice changed dramatically following the efforts of an abortion policy committee—largely spearheaded by Doctor #1 and Doctor #2, respectively faculty members of the university’s departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology (“Ob/Gyn”) and Family Medicine—to have UNM become a provider of abortions beyond the former limited circumstances.2

The doctors’ objective met with opposition from upper-level UNM Hospital administrators, who told them, among other things, that UNM policy prohibited abortions at university clinics, that the hospital would not subsidize abortion, and that nurses would not want to participate in any aspect of abortion.3

Over the course of about a year and a half, the doctors pressed ahead with their agenda, disregarding the admonitions of administrators and reservations of most of the hospital staff who did not wish to be implicated in abortion practice. In 2002, the doctors succeeded in introducing medical abortion—through the use of mifepristone, or RU-486—into UNM clinics.

The doctors then pressed further, against additional resistance by administrators, until they successfully introduced surgical abortion into UNM clinics. To do this they overrode objections of clinic staff, despite acknowledging that such opposition “may be intense, particularly due to the more extensive patient interaction required for surgical procedures and the increased complexity of the procedure.” By that point, however, the doctors, whose salaries are paid by the taxpayers of New Mexico, were disinclined to accommodate such moral qualms, dismissively writing in a published article that while they “anticipate hiring dedicated nurses and support staff . . . . abortion opponents have limited rationale to prevent MVA [manual vacuum aspiration] for pregnancy termination.”6

The Panel’s footnotes refer to an article, cited but not included in the released documents. In the article, the doctors write their own story of how they masterminded the plot to bring unfettered abortion to the university. The authors are Dr. Eve Espey, the current chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology (OB-GYN) and Dr. Lawrence (Larry) Leeman, a professor at UMN who works in both the OBGYN department and the Family Medicine Department. Espey arrived at UNM in 1997, Leeman in 1999 (page 79). By 2000, the mission to make New Mexico abortion central was in progress.

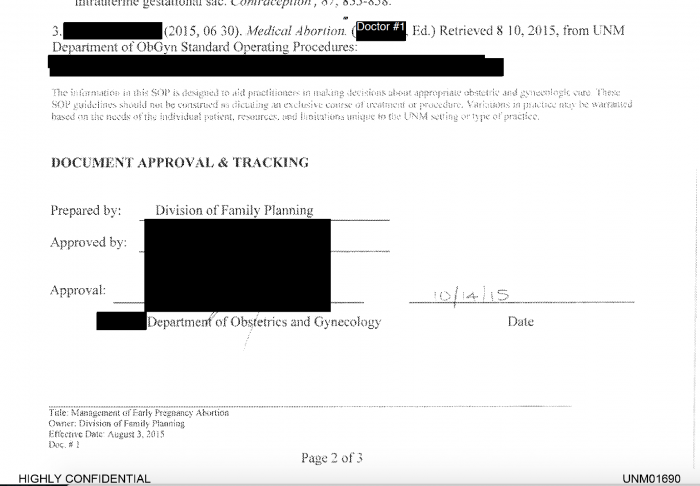

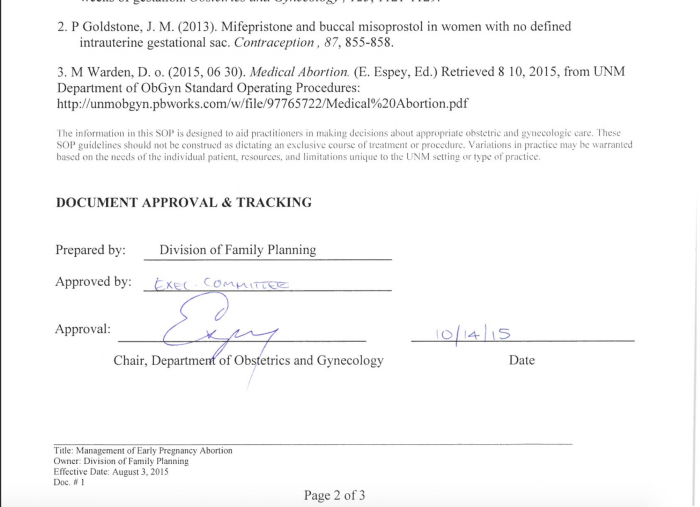

While the Panel did not make public the names of the doctors and researchers implicated in the investigation, the information is available via cross-checking of public records, such as these redacted forms with references to doctors, which can be matched with the actual forms housed on UNM’s own website:

However, in the case of Espey and Leeman, they wrote their own narrative for Contraception, a peer-reviewed medical journal, so there can be no question of their involvement, for they published it—and others—chronicling their journey and identifying themselves not only as authors, but also as participants, as they explain how they partnered to bring prolific abortions to the university (referring to themselves with their initials):

The collaboration between the departments of FM [Family Medicine] and Ob/Gyn was crucial to our success in introducing medical abortion. We were fortunate to have an effective liaison (LL) between the departments. He completed an Obstetrics fellowship, has a dual appointment in FM and Ob/Gyn and spends considerable time on labor and delivery with patients, residents (FM and Ob/Gyn) and medical students. He has become well known and accepted by Ob/Gyn residents and faculty. The Ob/Gyn faculty member (EE) directing abortion training and services has an extensive history of working with FM faculty and teaching FM residents.

The Panel documents note Espey and Leeman fought against every challenge until they introduced medical abortion into UMN clinics. Their co-authored journal article in Contraception is entitled “You can’t do that ’round here”: a case study of the introduction of medical abortion care at a University Medical Center.” This is what the Panel is footnoting that actually was not released in its documents.

From Espey and Leeman’s article in Contraception, detailing the timeline of bringing abortion to UMN.

The article details the beginning, starting with the battle to convince all the nurses and pressure the administration (emphasis added):

The provision of abortion services is an important aspect of women’s health care…. Upper level administrators of UH explained that we could not offer abortion services at UNM clinics because of a policy that prohibited abortion care in UH clinics. We asked to see the policy. A lengthy standoff occurred. The administrators continued in their assertion that we could not offer medical abortion without their approval. They were unable, however, to produce the written policy prohibiting abortion care services. Numerous other reasons were cited to discourage us from pursuing the introduction of medical abortion. These reasons included the concern that no nurses would wish to be involved in any part of the procedure and that the hospital would not subsidize abortion.

If you can’t beat them, bully them. This was the tactic Espey and Leeman employed. They write (emphasis added):

After 6 months of delays, we announced that we would begin offering medical abortion in 1 month unless we received a written prohibition. We assured the hospital administration that only willing nurses would participate in the care of patients seeking medical abortion and that the hospital would not be asked to subsidize abortion. We soon received a terse response that the UH would allow us to offer medical abortion. The response reiterated the requirement that the hospital would not subsidize the service…. When we began offering medical abortion in the clinics, our impression was that a significant minority of staff remained hostile and angry. Over time, we believe that staff has become accepting of the provision of these services.

They don’t note what made them believe such a thing or why they think their personal beliefs belong in an article in a scholarly journal, but they say so nonetheless. Perhaps the real reason the staff stopped protesting was that it realized it could not fight back since it was being done already, or perhaps, if they were subordinates, they felt intimidated. Whatever the reason, the physicians published that they “believe” the staff became more open, though they offer no evidence of this change.

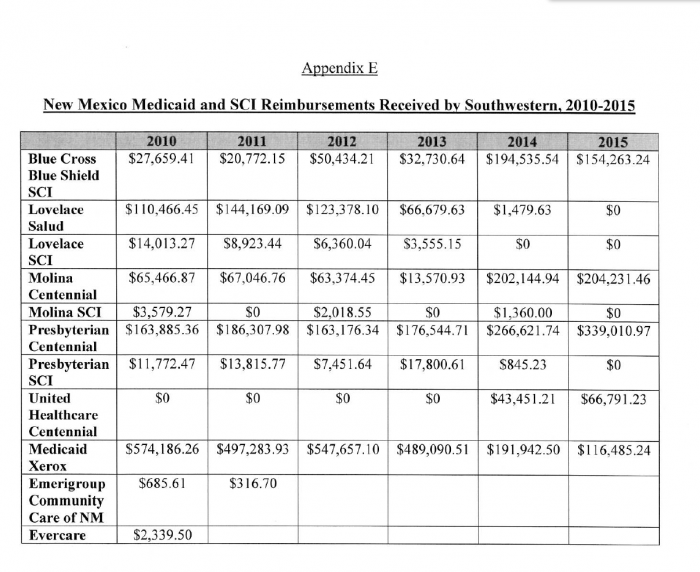

Meanwhile, Espey and Leeman also didn’t need the university’s hospital to subsidize the abortions because they let the state government take care of that. They write:

New Mexico Medicaid has paid for medically necessary surgical abortions since 1995. In 2003, this coverage was extended to medical abortion. Medicaid is the most common form of insurance for women seeking reproductive services in New Mexico. Medicaid coverage of medical abortion has reduced the financial barrier to abortion access for many of our patients. Most other insurance carriers cover mifepristone as well. The largest uninsured group in Albuquerque consists of the recent immigrants from Mexico who are ineligible for Medicaid until they have lived in the state for 5 years. Women whose insurance does not cover medical abortion may receive partial coverage for the prenatal visit, labs and ultrasound. These women are required to pay for the mifepristone at the time of service in accordance with our agreement with administration.

And before the partnership with Curtis Boyd’s late-term abortion facility (detailed in the Panel’s document), the university was already partnering with Planned Parenthood. In their abortion story, they explain how they began putting medical students on abortion rotations:

Residents spend a full day at Planned Parenthood and half days at the Family Practice Reproductive Clinic as well as at a private family physician’s office. The Ob/Gyn interns spend one-half day per week at the Ob/Gyn Family Planning Clinic and are scheduled for 8–10 abortion training sessions at Planned Parenthood during their second year.

These rotations continue, according to their website.

Espey and Leeman’s 2005 article also previews their plans to add surgical abortion, which they successfully implemented, virtually without restriction. They write in the article (emphasis added):

The next step in our plan … is the introduction of surgical abortion services…. Objections by clinic staff may be intense, particularly due to the more extensive patient interaction required for surgical procedures and the increased complexity of the procedure. We anticipate hiring dedicated nurses and support staff. We do believe, however, that since we are currently offering medical abortion and MVA for early pregnancy loss, abortion opponents have limited rationale to prevent MVA for pregnancy termination.

There is little room in Espey and Leeman’s writing for opposing views. As chair of OB-GYN, Espey fights to ensure that her medical students become abortionists. Both doctors show they are abortion activists, on a mission to turn a public hospital and a public research university into a breeding ground of dead babies, whose parts are more valuable than their whole.

Espey and Leeman are the masterminds behind the university-sanctioned bloodshed, continuing to influence others and multiply themselves even as they snuff out life in the name of education and research.