Abortion activist secures removal of pro-life billboards in British Columbia

Bridget Sielicki

·

FACT CHECK: Is South Carolina’s pro-life law to blame for denial of a post-miscarriage D&C?

A woman in South Carolina told PEOPLE she was denied miscarriage care following the loss of her “very wanted” baby… because of the state’s pro-life law.

Elisabeth Weber told the magazine that she was pregnant with her fifth child after losing her son Stone to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) in 2018. She and her husband, Thomas, were excited to be pregnant, but on March 27, at nine weeks pregnant, she learned that her baby, Enzo, had tragically stopped growing at about six weeks. She said her OB/GYN told her it was “most likely a miscarriage.”

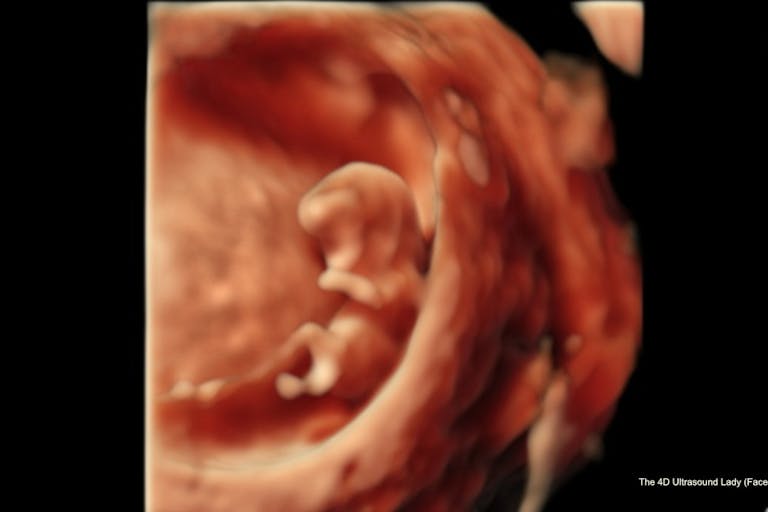

No heartbeat detected

When Weber had that first ultrasound at nine weeks, no heartbeat could be detected.

The next day, she experienced cramping, and her OB reportedly told her to go to the ER. A scan there again showed that there was no heartbeat. However, Weber was still dealing with the symptoms of being pregnant, including extreme morning sickness called hyperemesis gravidarum (HG).

“My body was not recognizing that I wasn’t pregnant anymore,” she said. “I was still completely bedridden with nausea, throwing up all the time.” Four days later, on March 31, she returned to the ER in pain and on the advice of her OB. She was again told that there was no heartbeat at nine weeks and three days.

It seems from Weber’s video testimonial that she returned to the ER once again — and this is when she appears to have requested a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure, in which the remains of the baby and placenta are scraped or suctioned out of the uterus to complete the miscarriage. She was still experiencing extreme nausea. “With my HG and all of that, I’m so sick,” she said. “I have three kids, and waiting around to go into a mini-labor is just hard.”

However, she claims doctors at the ER told her, “Because of the law — the heartbeat bill — we legally have to wait.”

She said, “My baby didn’t have a heartbeat, and it still prevented me from getting care,” adding that she was asked if the pregnancy was “wanted.”

“And I was like, ‘Yes, it’s very much wanted.’ She seemed to be implying that I was trying to sneakily get rid of it. Obviously, that was not the case. I looked at her and literally was like, ‘My baby is dead. Every doctor I’ve talked to knows my baby is dead. My baby is not going to magically get a heartbeat.'”

Weber was told that in order to get a D&C, she would need to wait, but to come back if she “started heavily bleeding, like hemorrhaging.” However, in a TikTok video, Weber said that doctors told her that they had to wait two weeks to ensure there was no heartbeat.

“My baby has been sitting inside me dead for three weeks already,” Weber said in a tearful and heartbreaking TikTok video during which she said had to wait another week knowing my baby is dead to do anything about it.” She also stated that she was “raised in a cult and was forced to stand in front of abortion clinics as a CHILD,” and made sure to point out that she is “not conservative and… did NOT vote for trump.”

She told PEOPLE, “I can’t believe that I’m being forced to carry around my dead baby. They know it’s gone, they know it’s dead, they know it’s stopped developing, and now I’m being forced to carry it … there’s really no feeling like when your womb becomes a tomb.”

After sharing her story on TikTok, a patient advocate contacted her and told her to go to a different hospital. She did, and was told her white blood cell count was high, yet that hospital told her she didn’t meet the requirements for a D&C.

“I was still in a ton of pain, but they just sent me home with Oxycodone,” Weber says. “I felt like I couldn’t even grieve … I haven’t even had a moment to just sit and mourn this.”

After two weeks, she was able to undergo the D&C, telling PEOPLE that on her paperwork, “it says abortion.”

South Carolina law

South Carolina’s Fetal Heartbeat and Protection from Abortion Act states that “abortions may not be performed in this state after a fetal heartbeat has been detected except in cases of rape or incest during the first twelve weeks of pregnancy, in medical emergencies, or in light of a fatal fetal anomaly.”

Article continues below

Dear Reader,

In 2026, Live Action is heading straight where the battle is fiercest: college campuses.

We have a bold initiative to establish 100 Live Action campus chapters within the next year, and your partnership will make it a success!

Your support today will help train and equip young leaders, bring Live Action’s educational content into academic environments, host on-campus events and debates, and empower students to challenge the pro-abortion status quo with truth and compassion.

Invest in pro-life grassroots outreach and cultural formation with your DOUBLED year-end gift!

The law defines “abortion” as “the act of using or prescribing any instrument, medicine, drug, or any other substance, device, or means with the intent to terminate the clinically diagnosable pregnancy of a woman with knowledge that the termination by those means will, with reasonable likelihood, cause the death of the unborn child. Such use, prescription, or means is not an abortion if done with the intent to save the life or preserve the health of the unborn child, or to remove a dead unborn child” (emphases added).

In addition, Section 44-41-330 of South Carolina law states, “If an ultrasound is required to be performed, an abortion may not be performed sooner than sixty minutes following completion of the ultrasound” (emphasis added).

This is very different from the two-week timeline that Weber said doctors gave her.

Her baby did not have a heartbeat and the law is clear that it protects living preborn children from induced abortion — direct and intentional killing — when there is a detectable heartbeat. It is also clear that under the law, an act is not an abortion if used to “remove a dead unborn child.”

After examination, it does not appear that the state’s pro-life law was to blame for the emergency room’s denial of a D&C at that point in time.

Weber’s grief is real and heartbreaking, and navigating the circumstances surrounding a miscarriage can be frightening and overwhelming.

What might have happened

There are circumstances in which a heartbeat is not detectable at first, but upon a follow-up exam, it is. This has happened to women countless times, as there are reasons other than miscarriage that a heartbeat might not be detected. This includes that the dating of her pregnancy could have been off, and in another week, there could be a detectable heartbeat.

According to Parents, “If your provider doesn’t hear a heartbeat, they’ll assess you for other possible miscarriage symptoms. If they don’t find any, rechecking with another ultrasound after seven to 10 days is the most common recommendation.”

Hospital staff could have been considering this possibility in their decision to hold off on a D&C for Weber because, although she was experiencing pain and cramping, she was not bleeding, and her membranes did not appear to have ruptured.

In addition, a D&C is not the go-to response to an early miscarriage. According to the American Pregnancy Association, about half of women who miscarry do not undergo a D&C. “Women can safely miscarry on their own with few problems in pregnancies that end before 10 weeks,” it states on its website. “After 10 weeks, the miscarriage is more likely to be incomplete, requiring a D&C procedure.”

It continues, “A D&C may be recommended for women who miscarry later than 10-12 weeks, have had any complications, or have medical conditions in which emergency care could be needed.”

Standard protocol appears to show that Weber may not have met the criteria for an emergency D&C at the time that she requested it.

A D&C procedure comes with risk of hemorrhage, infection, perforation or puncture of the uterus, laceration or weakening of the cervix, scarring of the uterus or cervix, and an incomplete procedure that requires a second procedure. If scarring of the uterus occurs, it may affect future fertility; a D&C may also increase the chance of preterm birth. A D&C procedure may be used to treat certain conditions in addition to missed or incomplete miscarriage. A D&C procedure may also be used to abort a still-living preborn child.

As for “abortion” being listed on Weber’s paperwork, miscarriage is typically charted medically as a “spontaneous abortion” — often to the dismay of mothers experiencing pregnancy loss. It is the act of an induced abortion — which is when such a procedure is carried out with the intention of causing the baby’s death — that is prohibited in South Carolina.

These hospitals that Weber visited have a medical protocol for an early miscarriage, but it has become clear that most Americans do not understand this protocol, and the fear and pain experienced during a miscarriage can understandably contribute to the tension and confusion in these circumstances.

Unfortunately, the media has not helped to assuage fears; it has exploited tragic miscarriage stories in an attempt to turn people against laws that protect preborn children from being intentionally killed.

Live Action News is pro-life news and commentary from a pro-life perspective.

Contact editor@liveaction.org for questions, corrections, or if you are seeking permission to reprint any Live Action News content.

Guest Articles: To submit a guest article to Live Action News, email editor@liveaction.org with an attached Word document of 800-1000 words. Please also attach any photos relevant to your submission if applicable. If your submission is accepted for publication, you will be notified within three weeks. Guest articles are not compensated (see our Open License Agreement). Thank you for your interest in Live Action News!

Bridget Sielicki

·

Fact Checks

Nancy Flanders

·

Fact Checks

Nancy Flanders

·

Fact Checks

Cassy Cooke

·

Fact Checks

Madison Evans

·

Fact Checks

Nancy Flanders

·

Issues

Nancy Flanders

·

Human Interest

Nancy Flanders

·

Investigative

Nancy Flanders

·

Pop Culture

Nancy Flanders

·

Human Interest

Nancy Flanders

·