Recently, controversy erupted after scientists announced that they had successfully altered human genes with the intent of eradicating some genetic health conditions. What made this controversial is the fact that scientists were creating embryos — human lives — solely to experiment on them, and then destroy them.

One of the three lead authors of a policy statement recommending that such research into editing human genes continues — published in the American Journal of Human Genetics — was interviewed by Medical Xpress. Kelly Ormond, MS, professor of genetics at the Stanford School of Medicine, spoke about the process and about why the statement was released now, as well as some of the ethical concerns surrounding the research.

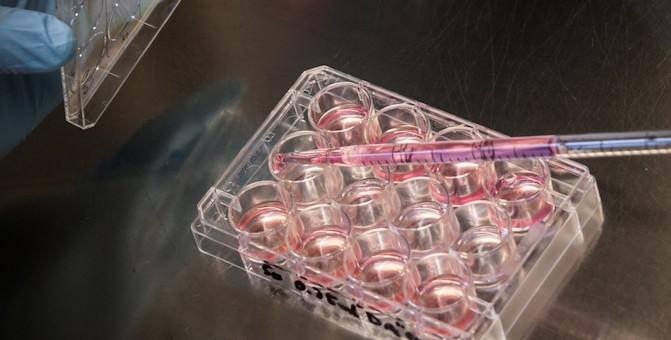

“We’ve been able to alter genes for many years now, but the new techniques, such as CRISPR/Cas9, that have come out in the past five years have made it a lot easier, and things are moving fast. It’s now quite realistic to do human germline gene editing, and some people have been calling for a moratorium on such work,” she explained. “Our organization, the American Society of Human Genetics, decided that it would be important to investigate the ethical issues and put out a statement regarding germline genome editing, and what we thought should happen in the near term moving forward.”

Ormond is against the varying regulations throughout the world on editing human embryos — and she also is calling for this experimentation on human embryos to be federally funded. “[S]ince 1995 the United States has had regulations against federal funding for research that creates or destroys human embryos,” she said. “We worry that restricting federal funding on things like germline editing will drive the research underground so there’s less regulation and less transparency. We felt it was really important to say that we support federal funding for this kind of research.”

Ormond acknowledged that there aren’t many immediate uses for human germline editing — but no need to worry, she says: people who wish to ensure their babies don’t have genetic diseases, like cystic fibrosis, can just abort them!

“Germline editing doesn’t have many immediate uses,” she admitted. “A lot of people argue that if you’re trying to prevent genetic disease (as opposed to treating it), there are many other ways to do that. We have options like prenatal testing or IVF and pre-implantation genetic testing and then selecting only those embryos that aren’t affected. For the vast majority of situations, those are feasible options for parents concerned about a genetic disease.”

It’s yet another symbol of how ableism is alive and thriving today. People with disabilities or genetic disorders like Huntington’s disease or cystic fibrosis are clear victims of eugenics already, and should this kind of research move forward, it will only get worse. No longer will funding be directed towards finding viable treatment for these conditions; instead, it will be used to prevent these people from existing, by murdering them when they are at their most vulnerable. We only have to look at what has already happened.

Disability rights advocate Rebecca Cokley

Disability self advocates, not surprisingly, have been speaking out against the idea of removing people with disabilities from the human germline. One of them is Rebecca Cokley (pictured), a woman with dwarfism, a disability rights activist, and a former member of the Obama administration. She is also the executive director of the National Council on Disability. In an op-ed for the Washington Post, she pleads with scientists not to edit people like her out. Cokley notes that 1 in 5 Americans has a disability, and that the news of human germline editing broke on the anniversary of the Americans with Disabilites Act, meant to put a stop to discrimination against people with disabilities. Yet the discrimination clearly continues. “Stories about genetic editing typically focus on ‘progress’ and ‘remediation,’ but they often ignore the voice of one key group: the people whose genes would be edited,” she said. “That’s my voice. I have achondroplasia, the most common form of dwarfism, which has affected my family for three generations. I’m also a woman and a mother — the people most likely to be affected by human genetic editing.”

While advances in science and medicine can be beneficial for people with disabilities, many disability rights groups react in fear when genetic links to disability are discovered, as Cokley pointed out:

I remember clearly when John Wasmuth discovered fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 in 1994. He was searching for the Down syndrome gene and found us. I remember my mother’s horrified reaction when she heard the news. And I remember watching other adult little people react in fear while average-height parents cheered it as “progress.”

How, if you are an average-height parent, do you explain to children whom you’ve spent years telling are beautiful the way they are, that if you could change them — fix them in a minute — you would?

Tampering with human genes doesn’t make the human race stronger or more fit for survival. Instead, it robs the world of people who are unique and valuable, and who make a difference… and all in the name of ableism. “[T]hink about the message that society’s fear of the deviant — that boogeyman of imperfection — says to disabled people: ‘We don’t want you here. We’re actively working to make sure that people like you don’t exist because we think we know what’s best for you,'” Cokley explained. “This is ableism. It’s denying us our personhood and our right to exist because we don’t fit society’s ideals.”

“Proponents of genetic engineering deliberately use vague language, such as ‘prevention of serious diseases,’ leading many people with disabilities to ask what, in fact, is a serious disease,” she continued. “Where is the line between what society perceives to be a horrible genetic mutation and someone’s culture?”

People with disabilities should not be prevented from existing due to backwards perceptions of what life should be. This is eugenics, plain and simple, and it should be condemned — not celebrated.

The method of gene editing, called CRISPR, was successful in 42 out of the 58 embryos created, but all 58 were still killed. There were countless other embryos also created and destroyed throughout the research process. This medical “breakthrough” was possible because human beings were created, purposely made to have genetic defects, experimented on, and then killed. Should this continue, then an already-disturbing trend of creating designer children through IVF and surrogacy will not only continue, but spiral out of control. And it will be done by taking lives.

There can never be anything ethical about that.